# =============================================================================

# Separate PLS Models Per Target

# =============================================================================

#

# Training one PLS model per target allows:

# - Better interpretability: each target has its own loadings showing which

# spectral regions are important for that specific compound

# - Independent optimization: each target can have its own optimal number of

# components

# - Potentially better performance: models can focus on the specific spectral

# regions relevant to each compound

target_names = ["glucose", "Na_acetate", "Mg_SO4"]

target_models = {}

target_optimal_components = {}

target_metrics_separate = {}

target_predictions_separate = {}

# Store single model metrics for comparison (from cell 11)

target_metrics_single = {}

for i, target_name in enumerate(target_names):

Y_target = Y[:, i]

y_pred_target = y_pred_final[:, i]

r2_target = r2_score(Y_target, y_pred_target)

rmse_target = root_mean_squared_error(Y_target, y_pred_target)

target_metrics_single[target_name] = (r2_target, rmse_target)

# Train separate PLS model for each target

for target_idx, target_name in enumerate(target_names):

print(f"\n{'='*60}")

print(f"Training PLS model for {target_name}")

print(f"{'='*60}")

# Extract single target

Y_target = Y[:, target_idx].reshape(-1, 1) # Reshape to (n_samples, 1)

# Find optimal number of components for this target

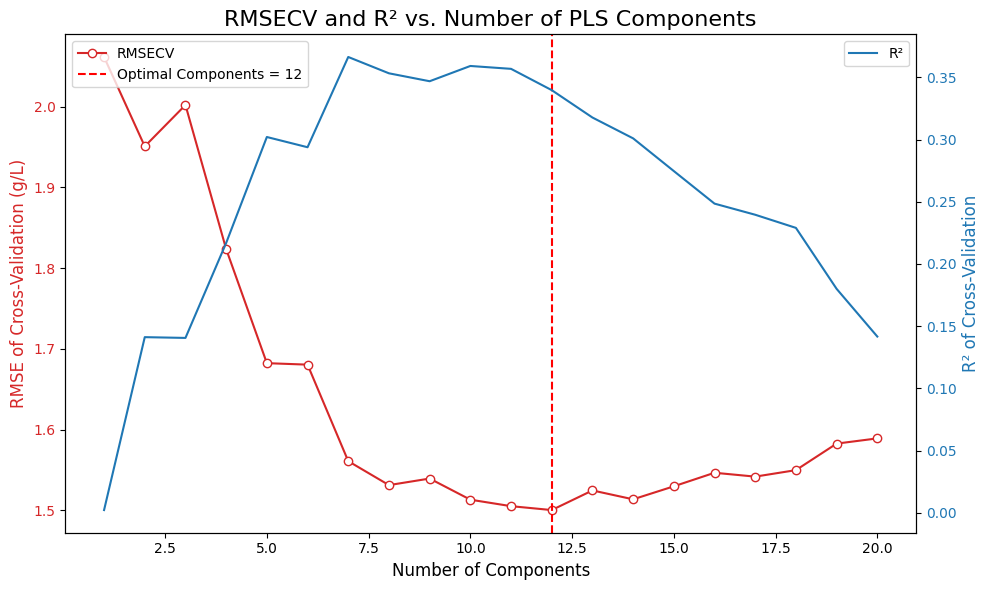

n_components_range = np.arange(1, 21)

rmsecv_scores = []

r2cv_scores = []

for n_comp in n_components_range:

pls = PLSRegression(n_components=n_comp)

y_pred_cv = cross_val_predict(pls, X_processed, Y_target, cv=cv_splitter, groups=groups)

rmsecv = root_mean_squared_error(Y_target, y_pred_cv)

r2cv = r2_score(Y_target, y_pred_cv)

rmsecv_scores.append(rmsecv)

r2cv_scores.append(r2cv)

print(f" {n_comp:2d} components: RMSECV={rmsecv:.4f}, R²CV={r2cv:.4f}")

# Find optimal number of components

optimal_n_components = n_components_range[np.argmin(rmsecv_scores)]

target_optimal_components[target_name] = optimal_n_components

print(f"\n Optimal components for {target_name}: {optimal_n_components}")

# Train final model and get cross-validated predictions

final_pls = PLSRegression(n_components=optimal_n_components)

y_pred_final_separate = cross_val_predict(final_pls, X_processed, Y_target, cv=cv_splitter, groups=groups)

# Calculate metrics

r2_final = r2_score(Y_target, y_pred_final_separate)

rmse_final = root_mean_squared_error(Y_target, y_pred_final_separate)

target_metrics_separate[target_name] = (r2_final, rmse_final)

target_models[target_name] = final_pls

target_predictions_separate[target_name] = y_pred_final_separate

print(f" Final R²: {r2_final:.4f}, RMSE: {rmse_final:.4f} g/L")

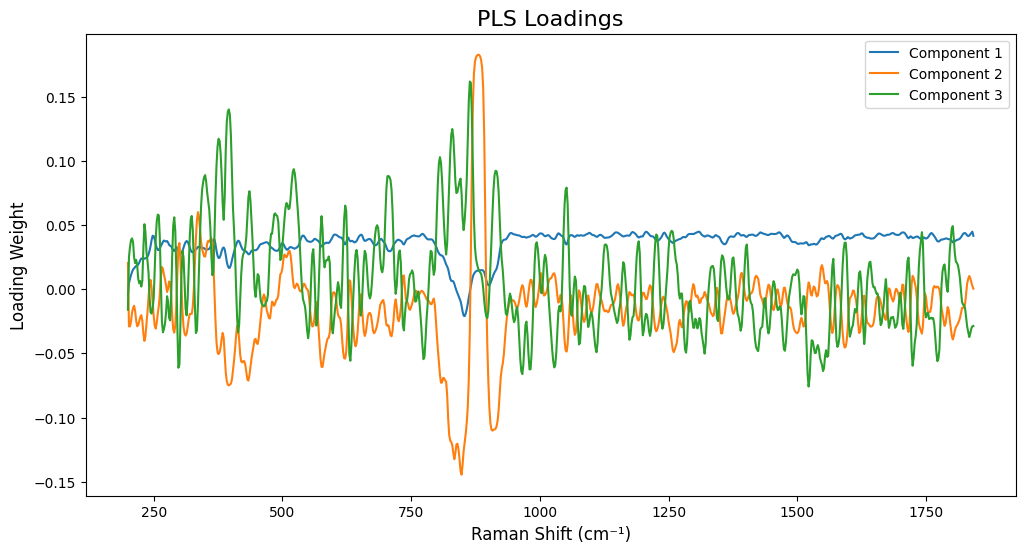

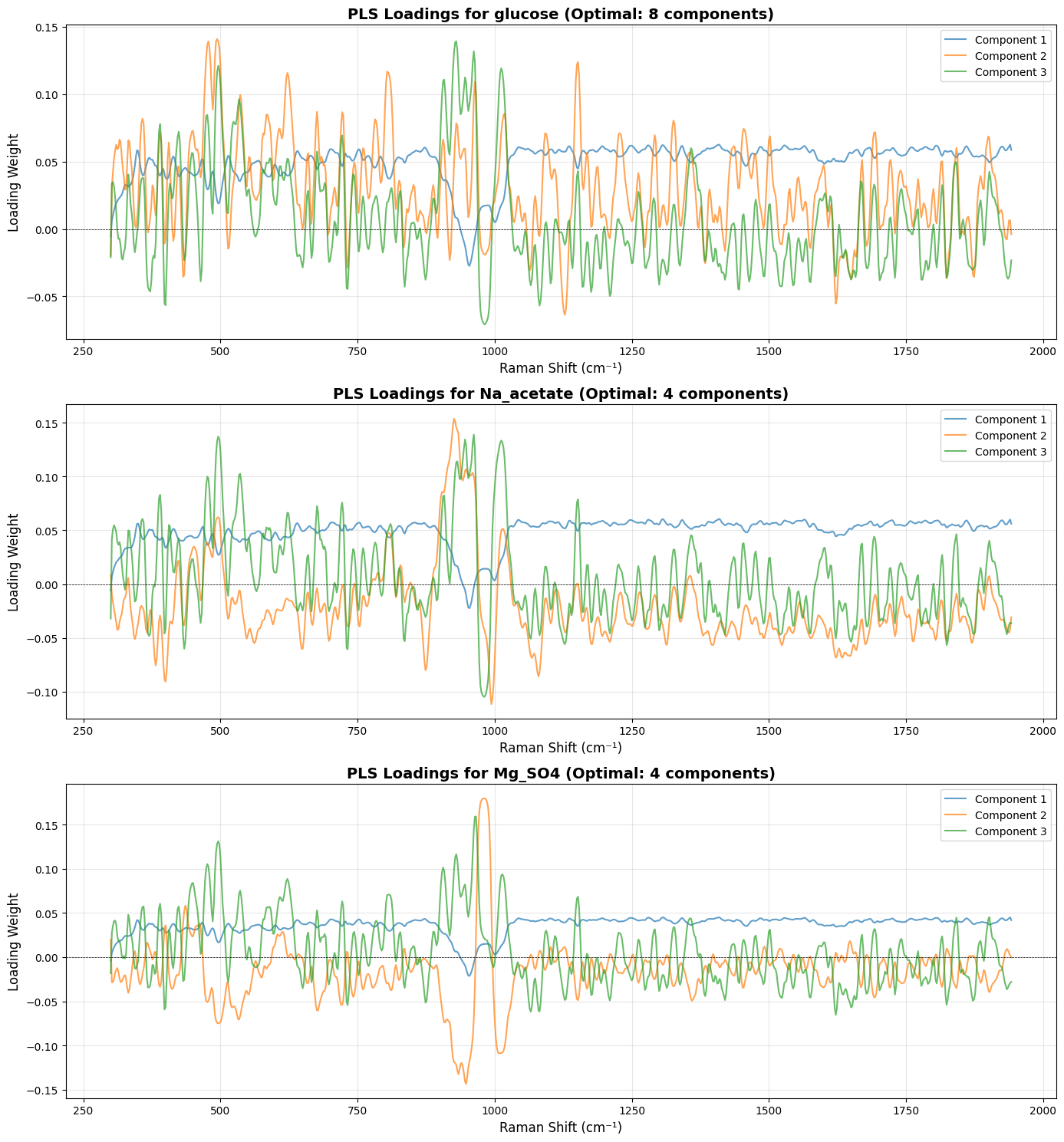

# =============================================================================

# Plot Loadings for Each Target (Much More Interpretable!)

# =============================================================================

fig, axes = plt.subplots(len(target_names), 1, figsize=(14, 5*len(target_names)))

# Handle case where we have only one target (axes would be 1D, not 2D)

if len(target_names) == 1:

axes = [axes]

for idx, target_name in enumerate(target_names):

model = target_models[target_name]

# Fit the model on all data to get loadings

model.fit(X_processed, Y[:, idx].reshape(-1, 1))

loadings = model.x_loadings_

# Use wavenumbers from processed spectra to match loadings dimensions

wavenumbers_processed = processed_spectra.spectral_axis

if hasattr(wavenumbers_processed, 'values'):

wavenumbers_processed = wavenumbers_processed.values

ax = axes[idx]

n_comp_to_plot = min(3, target_optimal_components[target_name])

for comp_idx in range(n_comp_to_plot):

ax.plot(wavenumbers_processed, loadings[:, comp_idx],

label=f'Component {comp_idx+1}', alpha=0.7, linewidth=1.5)

ax.set_title(f'PLS Loadings for {target_name} (Optimal: {target_optimal_components[target_name]} components)',

fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

ax.set_xlabel('Raman Shift (cm⁻¹)', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Loading Weight', fontsize=12)

ax.legend(loc='best')

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.axhline(y=0, color='k', linestyle='--', linewidth=0.5)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# =============================================================================

# Performance Comparison: Single vs. Separate Models

# =============================================================================

print("\n" + "="*80)

print("Performance Comparison: Single Multi-Output Model vs. Separate Models")

print("="*80)

print(f"{'Target':<15} {'Single Model R²':<18} {'Separate Model R²':<18} {'R² Improvement':<15} {'Single RMSE':<15} {'Separate RMSE':<15} {'RMSE Improvement':<15}")

print("-"*80)

for target_name in target_names:

single_r2, single_rmse = target_metrics_single[target_name]

separate_r2, separate_rmse = target_metrics_separate[target_name]

r2_improvement = separate_r2 - single_r2

rmse_improvement = single_rmse - separate_rmse # Positive = better (lower RMSE)

print(f"{target_name:<15} {single_r2:>17.4f} {separate_r2:>17.4f} {r2_improvement:>+14.4f} {single_rmse:>14.4f} g/L {separate_rmse:>14.4f} g/L {rmse_improvement:>+14.4f} g/L")

print("="*80)

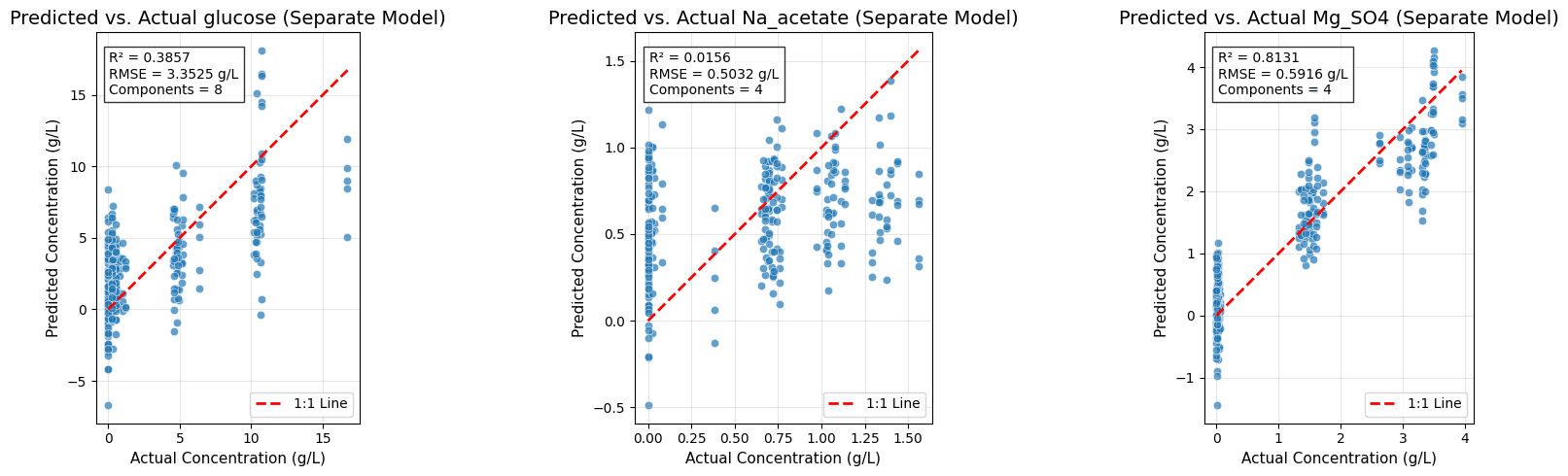

# =============================================================================

# Predicted vs. Actual Plots for Separate Models

# =============================================================================

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(18, 5))

for idx, (target_name, ax) in enumerate(zip(target_names, axes)):

Y_target = Y[:, idx]

y_pred_target = target_predictions_separate[target_name].flatten()

r2_target, rmse_target = target_metrics_separate[target_name]

sns.scatterplot(x=Y_target, y=y_pred_target, alpha=0.7, ax=ax)

ax.plot([Y_target.min(), Y_target.max()], [Y_target.min(), Y_target.max()],

'r--', lw=2, label='1:1 Line')

ax.set_title(f'Predicted vs. Actual {target_name} (Separate Model)', fontsize=14)

ax.set_xlabel('Actual Concentration (g/L)', fontsize=11)

ax.set_ylabel('Predicted Concentration (g/L)', fontsize=11)

ax.text(0.05, 0.95, f'R² = {r2_target:.4f}\nRMSE = {rmse_target:.4f} g/L\nComponents = {target_optimal_components[target_name]}',

transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=10,

bbox=dict(facecolor='white', alpha=0.8), verticalalignment='top')

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()